A guided tour of the Universe from Einstein to JWST

It was a great pleasure to be invited to the Charlbury Beer Festival in June 2023 to give a talk in the culture tent. The topic I chose to discuss was gravity, and more specifically how our best theory of gravity, Einstein’s theory of general relativity, gave birth to the field of cosmology almost a century ago. This post narrates the talk I gave.

Introduction

Cosmology is the physical science concerned with trying to answer some of the biggest questions out there: how did the Universe start? What is it made of? and what is going to happen to the Universe in the future?

But for most of human history, questions like those were more generally addressed by philosophy or religion, rather than by systematic scientific enquiry. That changed around a hundred years ago with the birth of general relativity in 1915.

The goal today is to tell you about the development of general relativity as our current best theory of gravity. I’ll discuss some of the problems with the theory that preceded it — Isaac Newton’s law of universal gravitation — and how general relativity solved those problems. I’ll outline some of the predictions of general relativity, and explain how it gave rise to the field of modern physical cosmology. I’ll finish by highlighting some of the open questions in cosmology, and how new telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Euclid satellite will go some way towards answering these questions.

Gravity according to Newton

To understand general relativity, we first have to understand what gravity is. Most people have the conception that gravity is a force which attracts massive objects together. This is the concept that underpins Isaac Newton’s theory of gravity, which he developed in 1687. Newton watched an apple fall to the ground and realised that the same force that drew the apple towards the ground also drew the Moon towards the Earth. This was one of the first times physics had been used to successfully link terrestrial and celestial phenomena.

Newton’s law of gravitation is simple. It states that the force of attraction between two objects (F) is proportional to the product of the two masses (m1, m2)and inversely proportional to the square of the distance (r) between them.

So, what’s the problem with this idea? Actually, very little.

Newtonian gravity provides a very good description of most easily observable gravitational phenomena, and it’s even used by cosmologists today for certain applications, due to its simplicity. It is valid in what we call the “weak field regime”, in other words, situations where the force of gravity is small. From the equation above, we can see that the force F will be small either when the masses involved are small, or the distance between the objects is large.

As a parenthesis here, note that cosmologists can be a bit misleading when talking about the magnitude of certain quantities; to a cosmologist, the mass of the Earth would generally be considered small. In human terms, of course, it is incredibly massive.

However, even in Newton’s time, there were some hints that this law was not quite correct.

Problems with the Newtonian theory

Firstly, in Newton’s law of gravitation, the gravitational force is transmitted instantaneously. This is something which physicists call “action at a distance”. Take a toy example of a planet orbiting a star, with the planet being at the same distance from its star as the Earth is from the Sun (1.5 x 1011 metres), and say I was a super-dimensional being capable of manipulating solar systems. I set up a device to measure the gravitational force between the star and planet, and then move the planet ten times further away from the star. My measuring device shows that the force decreases instantly as soon as I move the planet away, until it is one hundred times smaller than the starting value.

But the planet was already very far from the star — it takes light around eight minutes to travel between the two. So how come the gravitational force changes instantly? Does it travel faster than light?

Newton himself was greatly troubled by this problem, though he never found a way to address them. As we’ll soon see, we had to wait another 250 years or so before this difficulty could be addressed.

The second problem with the Newtonian theory was noticed in the mid-19th century. It was realised that the observed precession of the perihelion of Mercury’s orbit (change over time of the point in Mercury’s orbit when it is closest to the Sun) did not match with the prediction made by the Newtonian theory. At the time it was speculated that the mismatch was due to the presence of another undetected planet in the solar system, but nowadays the true reason is well understood.

Recall that we said that the Newtonian theory is valid in the so-called weak field regime, when masses are small and distances are large. Now consider the Mercury-Sun system. The Sun is a massive object, and when Mercury is at its perihelion, it is at the point in its orbit when it passes closest to the Sun. So, the distance between the two is also relatively small. This means that we are no longer in the weak field regime, and the Newtonian theory breaks down.

Lastly, Newton’s law provides no physical understanding of why the force of gravity should be proportional to the mass of the objects. Why mass? Why not shape, or colour, or whatever other property an object may possess?

All of these questions were successfully answered by Albert Einstein and the theories of special and general relativity.

Special relativity

Albert Einstein was a remarkable physicist. In 1905, at the age of just 26, he wrote four Nobel-prize worthy papers: one explaining Brownian motion and proving the existence of atoms, one explaining the photoelectric effect (for which he did win the 1921 Nobel Prize in physics) and two explaining special relativity. It’s the latter which is relevant to our discussion today.

One key stumbling block to Isaac Newton’s conception of the Universe was his notion that space and time are absolute — that there is a fundamental, mathematical sense of space and time, against which we can measure anything.

With the theory of special relativity, Einstein showed that this concept is incorrect. Special relativity tells us that any measurement of space, time or mass depends on the observer’s speed. The faster one travels, distances become shorter, clocks tick slower and masses become heavier.

This implies that, mathematically speaking, we cannot treat space and time as separate entities, but rather as a connected whole: spacetime.

Other important consequences of special relativity are that mass and energy are equivalent (as expressed in the famous equation E = mc2) and that nothing in the Universe can travel faster than the speed of light.

General relativity

It took Einstein a further ten years to develop the theory of general relativity, finally publishing it in 1915. The key advance that general relativity brought was that it generalised the concepts of special relativity to curved spacetimes.

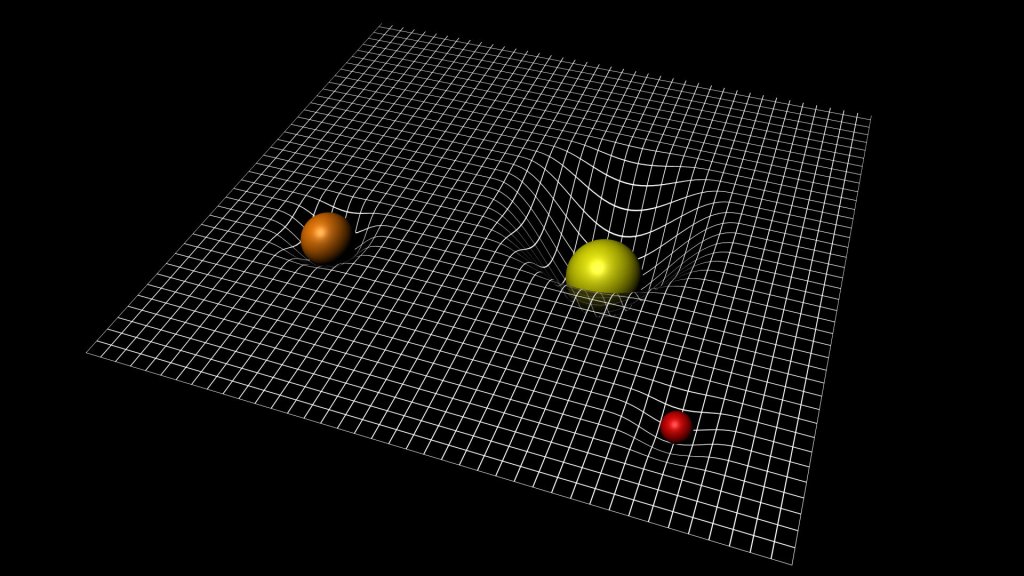

Einstein realised that, since mass and energy are equivalent, mass has the ability to change spacetime. Specifically, masses induce local curvature in spacetime.

Objects in spacetime move along geodesics — the shortest distance between two points. When spacetime is curved, the geodesics also become curved, meaning that one mass will follow the curvature of spacetime induced by another mass. This is phenomenon which we call gravity: objects falling along the curvature of spacetime.

So, how does general relativity resolve the problems with Newton’s law of universal gravitation? And what does it have to do with cosmology?

Firstly, revisiting the question of why the force of gravity should be proportional to the mass of the objects: we now know understand that gravity is curvature in spacetime induced by the presence of mass, so this proportionality is explained.

Secondly, the problem of action at a distance, or the force of gravity acting instantaneously. Special relativity tells us that there is a universal speed limit, the speed of light, and so that gravity must also travel at the speed of light. This was experimentally proven in 2017.

Lastly, the precession of Mercury’s perihelion. The full calculation in general relativity is long-winded, but it gives a value which exactly matches the observations. This is because general relativity correctly describes the behaviour of objects in strong gravitational fields, not just the weak field regime of Newton’s law.

First hint of general relativity’s success

Beyond filling in the gaps left by Newton’s theory, general relativity also made a staggering number of predictions, which were tested and confirmed over the following century. I won’t list all of them here, but rather just discuss those predictions which were most important for cosmology.

One of the first predictions of general relativity was that light will be deflected by massive objects. This is because particles of light — photons — travel through spacetime on geodesics, just like all other objects. This means that when the geodesics are curved in the presence of mass, light will follow that curvature.

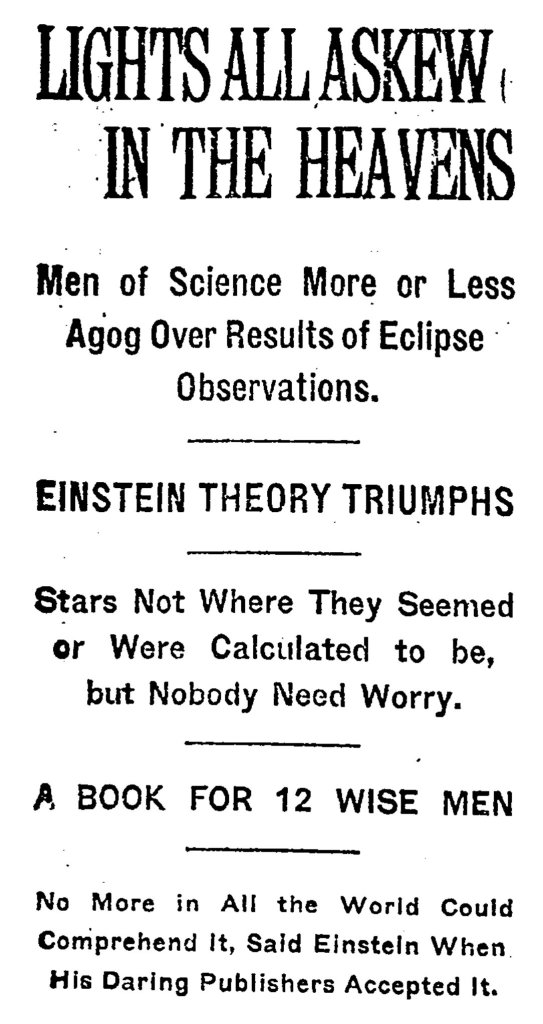

This prediction was confirmed by the astronomer Arthur Eddington in 1919. It was realised that the best way to look for light deflection by a massive object was to look at the positions of stars very close to the edge of the Sun, during a solar eclipse when the sky would be dark enough to see those stars. By comparing the positions of the stars in the sky during the eclipse with the positions of those same stars some months earlier at night, a small apparent change in positions was observed. This shift in position was due to the Sun’s gravity deflecting the light of the stars as it passed close by.

The observation of light deflection was a triumph for Einstein and the theory of general relativity. The predicted amount of light deflection was perfectly matched by the observations, and the confirmation of the theory made headline news around the world.

The simple deflection of light can also lead to the spectacular phenomenon known as gravitational lensing, where images of distant galaxies can be greatly magnified and distorted. Multiple images of the same object can also be seen. This phenomenon occurs when the object which is deflecting the light is very massive indeed — typically a galaxy or a whole cluster of galaxies — and the source object is bright — usually another galaxy. Finally, the two objects must be lined up with each other, and with us, the observers.

By observing gravitational lensing events with powerful telescopes, we can learn a lot about the structure and composition of individual galaxies. We can sometimes also glean information about the behaviour of spacetime itself — including its expansion rate. Yes, that’s right: general relativity predicts that the Universe should be expanding, and it was this crucial realisation that gave birth to modern cosmology.

The expansion of spacetime

Different solutions for the equations of general relativity describe different spacetimes. It was soon realised that the solution which best described our Universe based on its matter distribution — known as the Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker metric, after the people who found it — could only describe a Universe which was expanding or contracting.

This realisation posed a problem for Einstein. He, along with many other physicists at the time, believed that the Universe was static; it had existed forever in its current state, and would continue to do so forever. Einstein was so convinced of this that he modified the equations of general relativity to include an extra term which would force a static solution to be possible.

This was Einstein’s big mistake. In 1929, the astronomer Edwin Hubble made observations of distant galaxies. He quickly realised that the vast majority of galaxies are moving away from our own, and the further away a galaxy is, the faster it is receding. There was only one explanation for this: the Universe must be expanding. Einstein removed the extra term from the equations of general relativity, later calling it his “greatest blunder”.

The prediction of the expansion of spacetime and its subsequent observational proof was the moment that cosmology was born. Just like Newton two and a half centuries before, a beautiful and powerful connection had been made between an apparently localised phenomenon (gravity) and the behaviour of the entire Universe.

Waves in spacetime

The last prediction of general relativity that I’ll discuss is that of the existence of gravitational waves. Gravitational waves are ripples in spacetime, which are generated by very extreme events where the gravitational force is extremely strong. The most well-known scenario which produces gravitational waves is the merging of two black holes.

Einstein predicted the existence of gravitational waves at the same time as he formulated general relativity. However, despite the violence of the events in which they are usually generated, the effect of gravitational waves on the Earth is extremely tiny due to the extremely large distances from us at which the events occur. It took a hundred years before a detector sensitive enough to directly measure them could be built. This was the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO, in the United States.

The lasers inside the observatory are able to measure the distortions in spacetime caused by the passing of a gravitational wave. The laser arms are 4km long, and can measure distortions 10,000 times smaller than the width of the nucleus of an atom, which demonstrates the level of technology needed to observe these events. But observed they were, with the first gravitational wave event detected in 2016, exactly a century after Einstein predicted their existence.

Unanswered questions

Despite the success of general relativity, there are two very big unanswered questions in cosmology, both related to gravity on large scales: what is dark matter? and what is dark energy?

We can observe the detailed behaviour of stars in galaxies, and also how galaxies interact with each other, using gravitational lensing as well as other techniques. What we find is that the behaviour of stars and galaxies cannot be explained by gravity as we understand it with general relativity. For these objects to move and change as they do, there should be a lot more mass present in galaxies — mass which we cannot see. We call this unobserved mass dark matter. Its presence is needed to explain a whole host of observations, yet cosmology cannot provide a convincing answer for what it actually is, and it has also never been seen in a lab, or in particle collider such as the Large Hadron Collider at CERN.

Secondly, we recall that general relativity predicts that the Universe is expanding, and this was confirmed by observations in 1929. More recent and more precise observations of supernovae (exploding stars, chosen because they are very bright and thus relatively easy to observe) have revealed that the expansion rate of the Universe is speeding up. In general relativity, this does not make sense; we would expect the gravity due to the massive objects in the Universe to eventually slow down the expansion rate until the Universe collapsed in on itself. Instead, the opposite is happening: the expansion rate is accelerating.

We don’t know why this is happening. We simply attribute the effect to a mysterious “dark energy.” The Nobel Prize in physics in 1998 was awarded to Ada Riess and Saul Perlmutter for the discovery of dark energy, but a satisfying theoretical explanation for it has yet to be found.

The James Webb Space Telescope and the Euclid satellite

Open questions in cosmology like the true nature of dark matter and dark energy can be tackled in two different, yet complementary ways. Firstly, we can try to come up with new physical theories or laws which explain the observed behaviour of the Universe. This is the same way in which general relativity was developed.

Alongside new theories, we can make new observations, with the aim of gathering more information about these mysterious phenomena to help inform our theories. Two of the newest and most exciting observational projects are the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Euclid satellite.

JWST was launched on Christmas Day 2021, and is the natural successor to the Hubble Space Telescope. It has a bigger mirror and more advanced optics that Hubble, meaning the resolution of its images is much better. This makes it ideal for studying individual galaxies to learn more about the behaviour of dark matter and its role in galaxy formation.

The Euclid satellite is scheduled for launch on the 1st of July 2023. Its goal is rather different to JWST’s: it will survey nearly one third of the entire sky, taking measurements of galaxy shapes and positions. Over three years it will map around 1 billion galaxies. Since the observations will be on such a large scale and so wide ranging, we may be able to use them to distinguish between the different proposed theoretical models of dark energy, some of which have very subtle differences.

Conclusions

We have travelled from Isaac Newton’s law of universal gravitation in the 17th century to Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity and the birth of cosmology at the beginning of the 20th century, to the start of the 21st century where the final predictions of general relativity were confirmed at the same time that new questions began to be asked about the theory. As researchers, we are looking eagerly forward to the observational results of JWST and Euclid, and the possible answers they may provide to the biggest questions in the Universe.

Leave a comment